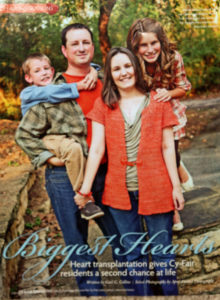

Like any teenager, Jordan Merecka did what he loved most in his free time: hunt during the season and fish all through the summer. Cy-Fair mom Brandy Parker was happily caring for her family and working s a bank teller. Both were born with heart defects, but managed to lead normal lives, until heart failure turned their worlds upside down. Merecka had to trade his Wranglers for a hospital gown, and Parked traded her role taking care of others for taking care of herself. Both also received life-changed operations that saved their lives and have allowed them to continue to thrive in our community.

Like any teenager, Jordan Merecka did what he loved most in his free time: hunt during the season and fish all through the summer. Cy-Fair mom Brandy Parker was happily caring for her family and working s a bank teller. Both were born with heart defects, but managed to lead normal lives, until heart failure turned their worlds upside down. Merecka had to trade his Wranglers for a hospital gown, and Parked traded her role taking care of others for taking care of herself. Both also received life-changed operations that saved their lives and have allowed them to continue to thrive in our community.

Reversed Heart

Merecka was born with multiple heart defects, including dextrocardia or a “reversed heart,” meaning his heart is located on the wrong side of his chest with the vessels facing backwards. After two open chest surgeries as a child and several surgical revisions, Merecka had a defibrillator implanted. Despite the doctor’s best efforts, his heart began to fail in September 2010, and he was placed on a waiting list for transplant surgery. With medical treatment, Merecka continued to attend Cy Wood High School.

Unfortunately, his condition progressed, and by April 2011, Merecka was admitted to Texas Children’s Hospital and quickly put on a ventilator before his major systems began shut down as well. Because both his ventricles had failed, he became a candidate for an artificial heart. “I had no other option, and it saved my life,” Merecka says. On May 22, 2011, Merecka became the first teen in the U.S. to have an artificial heart implanted in his chest at a pediatric hospital and one of three congenital patients in the nation to get such a device.

Artificial Heart, Real Lifesaver

The 15-hour surgery required Merecka’s native heart to be completely removed and replaced with the SynCardia Total Artificial Heart. The pneumatically driven heart precisely calibrates pulses of air and vacuum. Designed for advanced heart failure patients who might die before a transplant becomes available, the long term device serves as a bridge to transplant.

Pumping 9.5 liters per minute through both ventricles, Merecka’s artificial heart speeds recovery and builds strength for a future surgery when a donor becomes available. The average wait is 144 days for a heart. “The waiting game is tough,” says Merecka, adding, “But I feel 100 times better than before the artificial heart.” Despite the tough circumstances, Merecka doesn’t feel sorry for himself. “This is only temporary until they get a perfect match.”

Freedom Driver

Initially, Merecka was hooked up to “Big Blue,” a 418-pound console to run his artificial heart and required confinement in a hospital. In late August 2011, he became mobile with the Freedom Driver, a portable pack powered by lithium-ion batteries and weighing only 13.5 pounds. “I don’t feel any different with the artificial heart other than I have to carry a backpack around,” says Merecka. Now graduated and with increased freedom while he waits for a donor heart, Merecka plans to take college classes online with the hopes of one day soon attending Texas A&M.

Childhood Heart Problems

Parker’s heart problems began at a very early age. “I remember me family telling me that I had a hole in my heart, and at two years old, I quit breathing,” she recalls. Parker initially took heart medicine and lived a normal childhood, other than feeling like she couldn’t keep up in P.E. classes. She met her husband in high school, got married and started a family, welcoming a daughter in 2000 and a son three years later. Her daughter brought Brandy’s heart history back to the forefront of her health concerns.

At 2 weeks old, it was discovered that Brandy’s baby had three holes in her heart in addition to other problems. Caring for an ill child is stressful, and a few years later, Brandy passed out at work. “I was constantly tired, my hair was falling out, and I was overwhelmed with heat,” she says. After two days in the hospital, they decided she must have been worn down. But in 2007, while her daughter continued care, the doctor grilled Brandy about her own health. He insisted she be examined.

Diagnosis & Deterioration

Brandy was diagnosed with cardiomyopathy, a disease of the heart muscle that decreases its ability to pump blood. This condition is a major cause of heart failure. According to the American Heart Association, about 4.6 million people suffer from heart failure in the U.S., with 550,000 new cases occurring each year.

Parker began treatment with medication, but her health declined, causing fluid on her lungs. When her echocardiogram showed congested heart failure, Brandy says she become scared. “I heard nothing the doctor said after that—just blah, blah, blah—until the word ‘transplant.’ How did we go from taking a few pills to a heart transplant?”

In September 2009, Parker had a pacemaker with a defibrillator implanted, but by July 2010, her heart was deteriorating. She talked to patients in the hospital and prayed about whether to get a heart pump or go on the transplant list, but the decision was taken out of her hands. “I became upset, mad—a rollercoaster of emotions,” Parker says. She went on the transplant list in November 2010, and the call came in July 2011 that there was a 99.9% compatible heart. “It’s a scary process and a lifesaving process,” Parker says.

A Return to Life

Since her surgery, Parker participates in the Heart Exchange Support Group at Saint Luke’s Hospital where she meets with patients. “I can tell them to stay strong—it does get better.”

Parker lives a life of doctors, pills and immune issues in the aftermath of her heart transplant surgery. “It’s not a return to normal, but it’s a return to life,” she says. “It’s scary, humbling, and awe-inspiring all at the same time.” Then, Parker quietly adds, “Someone died so I could live.” She doesn’t know the 28-year old woman, Parker’s same age, of Dallas who donated her heart, but Parker says, “I will, in time; she was my angel. Without her, I wouldn’t have this chance to raise my children.” CFM

More than 3,000 Americans are currently waiting for a heart transplant. In the U.S., 18 individuals die each day waiting for an organ, but just one organ donation can save up to eight lives. You can provide someone a second chance at life by taking these two important steps to become an official donor:

- Join the organ donation registry in Texas by visiting donatelifetexas.org or ask about registration when renewing your driver’s license.

- Tell your friends and family of your decision, so they can let health specialists know if needed.

Source for statistics: Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network, optn.transplant.hrsa.gov