![]() September 2011

September 2011

Story & Photography by Gail G. Collins

Story & Photography by Gail G. Collins

Meeting Williamson Tapia, the bit of gray in his hair came as a surprise. The plein air painter’s enthusiastic, happy spirit had made him sound young. Chalk it up to a child’s energy walking around in a middle-aged man. “I want to work outside instead of a studio – to get out of the classroom. I get bored, and like a little boy, want to go out and play,” Tapia said, pointing through his window at the Red Rock scenery of Sedona.

Tapia was studying engineering before his love affair with plein air began in 1978, at age 19. He was attending Glendale Community College, and a few months after leaning to paint, his European-trained professor introduced Tapia to painting outdoors. The artist continued training at Arizona State University, where he received a Bachelor of Fine Arts in 1983, with post-graduate work at ASU West, focused on outdoor landscape painting.

The farms around Glendale were Tapia’s first subjects before embracing his Native American ties to paint tribal objects. He expanded his color palette with a move to Sedona in 1995. “I see perfect compositions everywhere, but I don’t want to just make pretty pictures,” Tapia said. “I respect the sanctity of the place, the precious opportunity to be there.”

Tapia’s style is direct study. Think of a still life. “Direct study is perceptual. The idea is to look at a thing and let the subject teach you how to understand it.”

Patronage of Tapia’s work grew into a four-year teaching stint at the Sedona Arts Center (SAC), and then, he sat on the board. This led to an invitation in 2005 to participate in Center’s Sedona Plein Air Festival. Two years later, Tapia won the Collectors’ Choice Award for Pendley Vista, a traditional plein air rendition of the ranch in Oak Creek.

Patronage of Tapia’s work grew into a four-year teaching stint at the Sedona Arts Center (SAC), and then, he sat on the board. This led to an invitation in 2005 to participate in Center’s Sedona Plein Air Festival. Two years later, Tapia won the Collectors’ Choice Award for Pendley Vista, a traditional plein air rendition of the ranch in Oak Creek.

Tapia took part in The Greatest Show on Earth during winter 2009-10, displaying his work alongside legendary artists Maynard Dixon and James Swinnerton. Such associations enabled him to compete in the plein air division of the Grand Canyon Celebration of Art in 2009 and 2010 as well as hold Artist-in-Residence status this past spring. “Our collective motivation is to preserve—to harmonize with the place and share the knowledge derived.” Stewardship is premium to Tapia. “We need to take care of the ‘Big Gift,’” he explained, referring to Earth. He joins the 2011 GC Celebration event again this month.

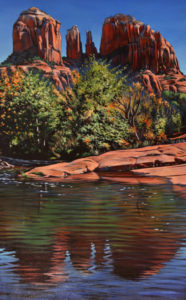

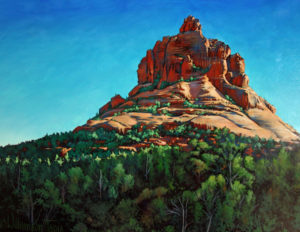

Paintings such as Sunset on Bell Rock began as a dark canvas on a panel. “I  try to build up the light areas first — like catching the sun coming up – adding layers gradually.” The soft lines of his paintings have a prescient feel. One senses the sweep of moments passing. “This is called compression study,” Tapia said. “There is the quality of time in the movement of light and shadow. The painting is alive.”

try to build up the light areas first — like catching the sun coming up – adding layers gradually.” The soft lines of his paintings have a prescient feel. One senses the sweep of moments passing. “This is called compression study,” Tapia said. “There is the quality of time in the movement of light and shadow. The painting is alive.”

The rusty rocks and surreal blue of an Arizona sky fill his large paneled works. In Grand Canyon Splendor as heather mists envelope pink points of rock, the landscape feels both mystical and touchable.

Plein air tempts artists with an outdoor communion of brushes and canvas. Tapia is quick to point out the other side. “It’s also challenging. The wind is a huge adversary. Many artists have seen their canvases fly like a sail into a canyon, and we share laughs about sitting on paint palettes.”

When it comes to organizational ties, Tapia called himself a rogue dog for his recent lack of them. And caught in life’s contradictories, Tapia is forming a group – The Society of Perceptual Artists –to push painters beyond their comfort zones by forgoing camera use to preserve their window of opportunity. In a purist biennial event culminating the first week in October at Yavapai College, participating artists contracted to practice plein air origins. Work is stamped with a camera with a line drawn through it.

A few relationships, along with Tapia’s Native American background, have inspired his purist attitude. Photography, or the “iron lens” as Tapia dubbed it, captures an image for study, but his beliefs claim it also robs the soul. So in 1997, Tapia ditched photo back-up. He prefers recursive study, returning to a place and time to grow his relationship with a subject.

Case in point, when Tapia painted Sunset at Yaki Point, the wind buffeted so he could barely hold his brush some evenings. “I had the set-up bungee-corded to my chair on one side and a tree stump on the other, and it still shook and shimmied. A good part of direct study plein air is learning when to wait and when to paint.” Sometimes he waits for hours or days for weather to clear. And the secret of Will Tapia? “Painting is a page out of my open journal – the retelling of my experience. NAMLM Gail G. Collins