Issue #118, 20 May 2014

Issue #118, 20 May 2014

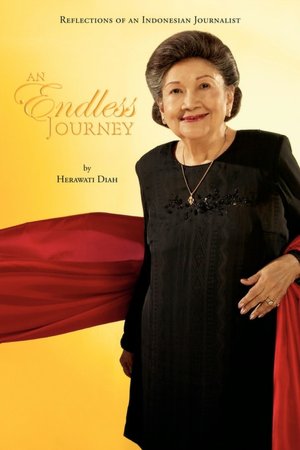

Story & Photography by Gail G. Collins

One doesn’t plan to live 97 years, but in doing so, it is impossible not to consider how it was accomplished, and moreover, what one contributed to the betterment of others during that lifetime. Herawati Diah has been described as the epitome of the Indonesian woman. Personally, she sees herself honouring traditional customs and a modern mind. This outlook translated as proud nationalism, when as a journalist, Herawati reported on Indonesia’s struggle for independence, and as an ambassador’s wife, she carried its culture abroad, and as leadership, she stood in the streets with women, urging them to find a strong voice. Benchmark moments in her life shaped her vision and steeled her steps for her book, An Endless Journey: Reflections of an Indonesian Journalist.

Gracious, poised, warm and welcoming, she encourages anyone who has met her through the years to say hello at gatherings. And people do. Thoughtful and still sharp, Herawati remembers details and inquires as to others’ wellbeing. Perhaps, this decorum is born of diplomacy, but more likely, it is her innate curiosity and concern for the larger world.

Born in 1917 into an upper class priyayi family, Herawati received a privileged education. Though other intellectuals travelled to colonial homelands in the Netherlands or Western Europe for school, her mother insisted her daughter study in Japan and America. “My independent spirit was fostered by my strong-minded mother,” Herawati said. She boarded with an American family to learn English and two years later, she attended Barnard College at Columbia University in New York. The seeds of journalism took root, and her career began.

As the first Indonesian woman to graduate from an American college, Herawati came home a star with her choice of jobs—even a movie offer—but she also returned to a homeland on the brink of war. She became a stringer for United Press International, but the position was cut short when Japan bombed Pearl Harbor. With a command of English, Herawati was pressed into service in Indonesia as an announcer at Radio Hosokyoku during the Japanese occupation. The insipid news was propaganda, but the job led to meeting her life partner, B.M. Diah, who worked at Asia Raya.

“He was good looking,” she said with a sly smile. They were married in 1942 and had three children. In August 1945, the Proclamation of Independence freed Indonesia and “merdeka” or “freedom” became the greeting on the street. It also became the banner on the newspaper B.M. founded. Its mission was to enrich the intellect of Indonesians.

“Journalism demands a love of work, but there are also tasks that require attention to our conscience,” she wrote in her memoir. Six months before the 1955 Asia-Africa Conference in Bandung, she founded the Indonesia Observer, the country’s only English newspaper for over a decade, providing a worldwide report for her people’s struggle.

In 1959, B.M. Diah received an ambassador posting in Czechoslovakia, and later Hungary, Thailand and Great Britain. Herawati packed cultural treasures from their home to introduce Indonesia to the world, even as their diplomatic journey introduced Herawati to kings, queens, presidents and statesmen. She left the business of reporting on Indonesia and began the job of representing it abroad with her integrity and intellect. Herawati noted as a journalist she had been a free spirit, but as a diplomat now, she must always be polite.

Her memories of meeting famous personalities are animated. She has known every Indonesian president, Queen Elizabeth, Franklin D. Roosevelt and Henry Kissinger. He quizzed her on communist China. Herawati once consulted Ghandi on Indonesia’s fight for freedom, and he said, “When you truly believe it will succeed, then it will surely succeed.”

B.M. became the Minister of Information in 1968, and their connections to world leadership continued. Seeing historical preservation abroad led Herawati to guard her homeland’s culture. She took her case to Paris and Borobudur Temple was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The pioneering woman also established foundations, such as Indonesian Cultural Partners to protect treasures and textiles, Indonesian Women’s Association and others, which raised political awareness in women. She never lost her nose for news, pushing women’s concerns in the 1990s. “They embody half of the world’s population,” she wrote, “hardly the affairs of a minority.” She still reaches out, working with a yayasan to educate young children.

If queried about who Herawati emulated, she said, “Anyone who can make our country free,” elaborating on equality in education, wealth and opportunity. She has travelled endlessly over the decades, always championing Indonesia and seeking to protect and progress it. Still, in her self-deprecating way, she said about her memoir, “At most, please regard this book as a record of events in which I was involved.” Yes, involved and motivated by a deep love of country.

Lastly, her secrets to a long life are not secrets at all, but the wisdom of the ages: Be strong, eat healthy—but not too much—live well and sleep well with no worries.

Gail G. Collins writers internationally for magazines and has co-written two books on expatriate life. She feels writing is the perfect excuse to talk to strangers and know the world around her better.

Gail G. Collins writers internationally for magazines and has co-written two books on expatriate life. She feels writing is the perfect excuse to talk to strangers and know the world around her better.