Northern Arizona’s Mountain Living Magazine, October 2018

Written by Gail G. Collins

As I climbed the steep, narrow, winding staircase of abandoned Mingus Union High School, a cool, but gentle, hand languidly brushed across my forehead. The hairs on my neck prickled, and my brows rose in wonder. I was not physically alone on the staircase, but neither was anyone within reach of me. The stairs brought me from the teachers’ dormitory to the main floor of the gymnasium where I stopped to consider what had just happened. The people ahead of me and behind continued upward without a care. Gooseflesh rose on my arms, as I recounted my ghostly encounter to the guide from Ghost Town Tours. Deadpan, he pointed out that the boys do love a pretty lady.

In the 1920s, the building was constructed to serve as Jerome’s new hospital, but it became the center for education for mining families. Today, the deserted property registers electromagnetic energy instead of students with activity spikes recorded in the boys’ shower and the whiff of cigarette smoke present in the girls’ area. My mind was open to things that defied explanation, but I wasn’t a ghost hunter.

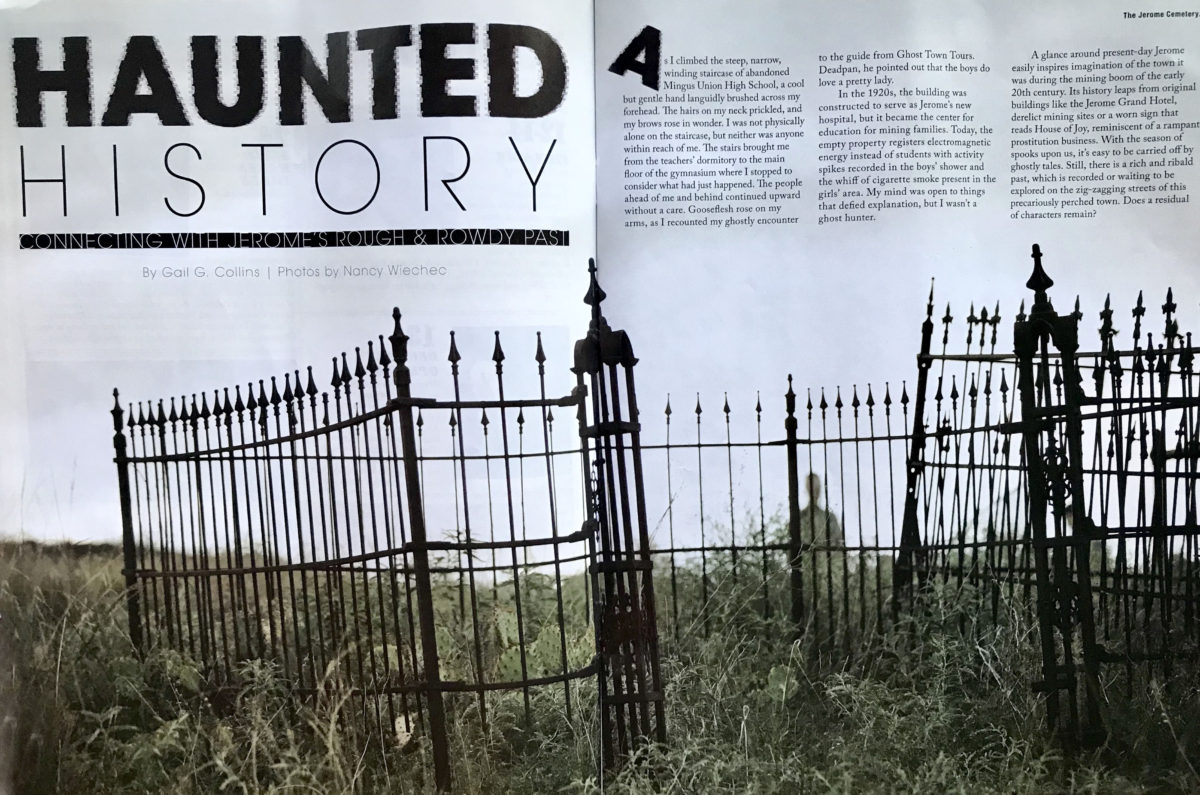

A glance around present-day Jerome easily inspires imagination of the town it was during the mining boom of the early 20th century. Its history leaps from original buildings like the Jerome Grand Hotel, derelict mining sites or a worn, painted sign that reads House of Joy, reminiscent of a rampant prostitution business. With the season of spooks upon us, it’s easy to be carried off by ghostly tales. Still, there is a rich and ribald past, which is recorded or waiting to be explored on the zig-zagging streets of this precariously perched town. Does a residual of characters remain?

Mining History

Originally, the Verde Valley was farmed by the Hohokam people, but Jerome has long been a place of mining. Whether it was those early tribes in search of ore for pigments, the Spanish conquistadors seeking gold or the two veins of copper that earned Arizona its nickname, the Copper State, the site suggested shiny value.

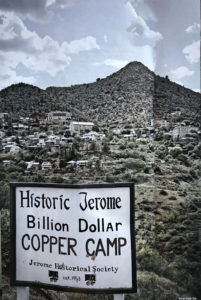

In 1876, the first mining claims were staked on two mounds that later would be called Cleopatra Hill and Woodchute Mountain. The result of tectonic plates pushing an ancient, undersea volcanic caldera upwards revealed two of the wealthiest ore deposits ever found, worth more than $1 billion. The stakes were purchased a few years later and organized as the United Verde Copper Company and bankrolled by Eastern financiers, including Eugene Jerome. A small mining camp began on Cleopatra Hill and was dubbed Jerome to honor him. Eugene Jerome was a relative of Jennie Jerome, mother of Sir Winston Churchill.

A few years later, the mine closed and was purchased by William A. Clark, whose successes in Montana mining carried over to assemble a profitable business venture in Jerome. He enlarged the smelter and built a narrow gauge railway. The company expanded to become the leading copper producer in the Arizona Territory, extricating nearly 33 million tons of copper along with zinc, lead, silver and gold.

The town boomed with ore production and accompanying population that grew from 250 to 2,500 by 1900. Four fires in as many years took their toll on the clapboard town, and new rules enforced the building of brick or stone structures on the main street. Landslides also impacted the hillside development. Jerome always rebuilt adding a post office, school, churches, civic organizations and plenty of commercial activity. Dangerous work encouraged dangerous entertainment, and a sizable chunk of those businesses—gambling halls, saloons and brothels—served the overwhelming numbers of men working the mines. In 1903, such unbridled, bawdy behavior earned Jerome the headline “wickedest town in the West” by the New York Sun.

The demand for copper soared with World War I, and additional mining companies produced a bonanza of ore. Little Daisy Mine, generated $10 million in 1916 alone. The population soared to nearly 15,000 inhabitants at its heyday with imported workers from 30 countries. Irish, Chinese, Italian, Slavic, Mexican and more nationalities were among the townsfolk.

Disaster & Dynamite

The influenza epidemic of 1918 significantly impacted Jerome with quarantines, closing businesses and schools and hundreds of deaths. The United Verde Hospital overflowed, and doctors set up temporary hospitals in three school buildings to handle the ill.

As the ore played out, mining open pits with blasting became routine. By 1953, the mines closed and Jerome’s population dropped to 100. With the town’s coarse exploits plus a pandemic, death had haunted Jerome more than other places. Mining accidents felled men and rowdy, rough living impacted bordello workers in the Cribs District or “Husband’s Alley.” A high dollar town promoted high stakes.

When it all collapsed, it seemed as if the townsfolk had walked away from their dinner tables and their lives in Jerome overnight. The vacant streets and shops held only the spirits of the past.

Ghosts

Now, it’s commonplace for hear reports of long lost souls connecting with Jerome residents or visitors. Some spiritual sightings, like Headless Charlie, emanate from mining accidents. The miner fell down a mine shaft and lost his head, but still reaches out to help others avoid calamity. Stories circulate of a woman, who was warned to stop riding her bicycle, but refused, and died in an accident soon after.

The ghost stories continue to write themselves as guests at the Jerome Grand Hotel fill a book each year with their phantom interactions. As Jerome’s premier hospital turned hotel, thousands died within its walls for various reasons. Today, haunting sounds abound, like keys rattling in locks, groaning, coughing, moving objects and spectral sightings of Claude Harvey, who died in a gruesome elevator accident. Connor Hotel rooms also attract spook naughtiness with an unplugged radio that turns itself on and ghostly apparitions.

Understanding Souls

Ghost Town Tours office manager Kay Chapman hears stories from people and has encountered manifestations in many forms. “Whether they are spiritual, residual or dimensional, it exists,” said Chapman. One day, as she worked, a shadowy, dapper, young man stood at her counter, waiting for something, but not speaking. He showed up for several days in a row for multiple weeks, except he wasn’t really there at all. On a foggy night, while working in the storeroom, Chapman looked up to find a sickly, grey, 4-year-old girl with a scarred face watching her. Another time, as she opened the office, someone walked in behind her and said, “Good morning.” When Chapman turned, no one was there. “There have been many occurrences,” she said. “It’s a steady flow of energy.” People, confused by their encounters, approach the tour manager to talk, relieved to find an understanding soul.

The Haunted Hamburger has specters that surprise staff and diners routinely. During initial renovations, hammers disappeared repeatedly. A previous tenant had experienced the same mystery. Later, the tools reappeared in odd locations. Perhaps, the tricksters were tradesmen from the former boarding house? Owner Eric Jurisin admitted, “Cans fly off shelves, the hot water turns on in the middle of the night, distinct smells arise in the stairwell and photographs taken by some guests have captured the wispy image of a woman.”

Ghost Town Tours offers electromagnetic field monitors to visitors, who seek some scientific proof of activity. I didn’t carry one. In the end, whether one believes the ghost stories is a matter of experience, for it is the experience that makes a believer of us.

Jerome today is a vibrant arts town with a thriving tourist trade, bolstered by Jerome’s Historical Society. Annually, they sponsor the Ghost Walk, to be held on October 12-13, during which visitors can participate in the eerie past. Tours and dramatic performances highlight history in “dreams, delusions and dastardly deeds.”

Beware, for spirits still roam the streets of Jerome. NAMLM