FlagLIVE! February 20, 2020

Photos and Story by Gail G. Collins

Our inclination toward a good thing is to enjoy and preserve it. For four decades, that’s been the case as coffee lovers consistently crowd Macy’s European Coffee House and Bakery, south of the tracks in downtown Flagstaff. The town’s first roaster and coffee house opened in 1980, and many who came to love it as students at Northern Arizona University are happy to see it just as they remember it all those years ago.

Owner Tim Macy, who prefers the term caretaker, feels that timelessness is part of the coffee shop’s intrinsic charm.

“Everyone is welcome in a spirit of unity—treated with respect and love,” he says. “Macy’s is a microcosm of what the world will be one day.”

With an easy smile, he then quips, “I got lucky—people loved Macy’s.”

It was more than luck; it was knowledge, determination and firm principles that propelled Macy’s idea to open a coffee house. It was also a man named Carl Diedrich, a German who had—after fighting at the Battle of the Bulge, marrying into a family coffee, tea and cocoa business, studying the coffee industry in Naples, Italy, and purchasing a coffee plantation in Guatemala—built a retail coffee business from his garage with a hand-fabricated roaster. Macy was inspired to learn from the innovator and self-taught man but initially struggled to reach him. Finally, he convinced Diedrich to teach him the trade when he showed up at his strip mall shop in Costa Mesa, California.

“Once a week, I would buy a pound of the best coffee I’d ever had in my life and hang around to learn the business,” Macy says.

Following what became a three-year mentorship, Macy chose to open his own shop in Flagstaff because of its college setting and great potential. He bought equipment and rented the space where Middle Earth Bakery had been. His first roaster, hand-built by Diedrich’s son, took center stage in the front window. In February 1980, with little more than a penny left to his name, Macy opened his doors.

At this point, Macy needed to educate the public about coffee. At the time, 99 percent of the best coffee was imported to Europe with a paltry amount making its way to the U.S. Macy would change that by serving 50-cent espressos and classy cappuccinos. People were captivated by the aroma of coffee roasting. It even caused a stir with the local fire department.

“For the first year, every few weeks, the fire department showed up, thinking there was a problem,” Macy recalls.

Diedrich supplied the coffeehouse with beans for 10 years before Macy began an alliance with Erna Knutsen. The “godmother of specialty coffee,” as she was known, traveled the world, reinvesting locally and promoting growers’ schools long before the advent of the fair-trade trend. Knutsen won the Specialty Coffee Association of America’s Lifetime Achievement Award in 1991, and was again honored as a founder of the specialty coffee industry in 2014. Today, Macy works with small-source farms, paying above fair-trade prices.

For all those reasons, Macy assures, “Now in Flagstaff, we have the best coffee in the world. You can find a similar product, but nothing better.”

Macy’s has long thrived on rare relationships. Early on, a gal applied for work at the coffee shop. As incentive, the budding artist flashed a sketch of a person, soaking in a cup of coffee bliss, drawn on a napkin. The student had limited availability so couldn’t be hired, but Macy paid her for the sketch, dubbed “the ultimate cup,” which became the shop’s logo.

Growing pains

Macy made a number of difficult but ultimately ground-breaking business decisions over the years.

In the early days, Macy’s tried selling a couple of Italian-inspired items, including gelato and handmade pasta, but coffee, pastries, sandwiches and soups forged its menu. And, after reading Diet for a New America by John Robbins, Macy became a vegetarian. Several members of his staff also refrained from eating meat, and Macy didn’t feel right having them handle roasted turkey each day. Soon after, the shop began serving only vegetarian cuisine.

“It was hard and sales took a hit, but then we became kind of a cool, unique place,” Macy says.

The vegetarian biscuits and gravy compete with meaty varieties for taste. Vegan Belgian-style waffles can be topped with fruit for a sweet treat. The French cinnamon roll within a croissant is doubly-good. All pastries are handcrafted daily by Siri Karshner with no preservatives, dough conditioners or stabilizers. Soup choices feature two daily specials.

“Macy’s makes the best grilled cheese in town,” 15-year coffee veteran Bill Gowey says during a recent visit.

Pair it with tomato basil soup for the ideal meal. Gowey rides his Victory Crossroads motorcycle across the U.S. stopping into coffee shops but maintains, “There is nothing like Macy’s.”

A welcoming atmosphere

Macy’s Baháʼí faith has influenced his business from the start and guides his interactions with employees and guests. General Manager Brandon Cox, soft-spoken in a knitted cap with a lumberjack-worthy beard, has worked for Macy for 19 years.

“It’s the spirit of the place—all walks of life can come together and jive,” he says. “It’s a philosophy of being kind to one another, and people feel that.”

Die-hard locals, running the gamut from high schoolers whose parents studied there as youngsters to retired folks, make up Macy’s customer base, coming in daily to get their caffeine fix.

“If we don’t see them, we wonder if they’re OK,” Cox says.

Cox credits the overall atmosphere at Macy’s with bringing customers back time and time again.

“We enjoy our work and have fun putting out a good product,” he says. “It’s the personality of the place.”

That personality starts with Macy himself, who Cox champions as compassionate, inspirational and kind, teaching him about the workplace and the world.

“He encourages individuality—it’s empowering,” Cox says.

Roasting relationships

Julia McCullough, a straight talker and old school Flagstaff admirer, has been roasting beans for Macy’s for 30 years. Like many employees, she began behind the counter and stayed because Macy’s became family.

“They’re an instant group of caring individuals,” she says.

McCullough roasts twice a week. The product, like the staff and clientele, is consistent, and that equation has long yielded success for Macy’s. The beans aren’t sold commercially, only in-house.

“A cup of Macy’s coffee is only available here,” McCullough says.

Usually, success breeds expansion, and Macy has been offered the chance to move or franchise many times. His answer was always no. Beyond growing its square footage in absorbing the shop next door, the coffee shop has remained exclusive; Macy isn’t about riches, and believes another location would split the spirit of the place.

“Keep it small; keep it unique,” he says. “That’s why we’re still here.”

Macy’s European Coffee House and Bakery will celebrate its 40th anniversary on Feb. 21. All day, coffee drinks will be half-price, and cake will be served until it’s gone. To commemorate the date, McCullough organized production of long-sleeve T-shirts and mugs designed by Robert Waldmire.

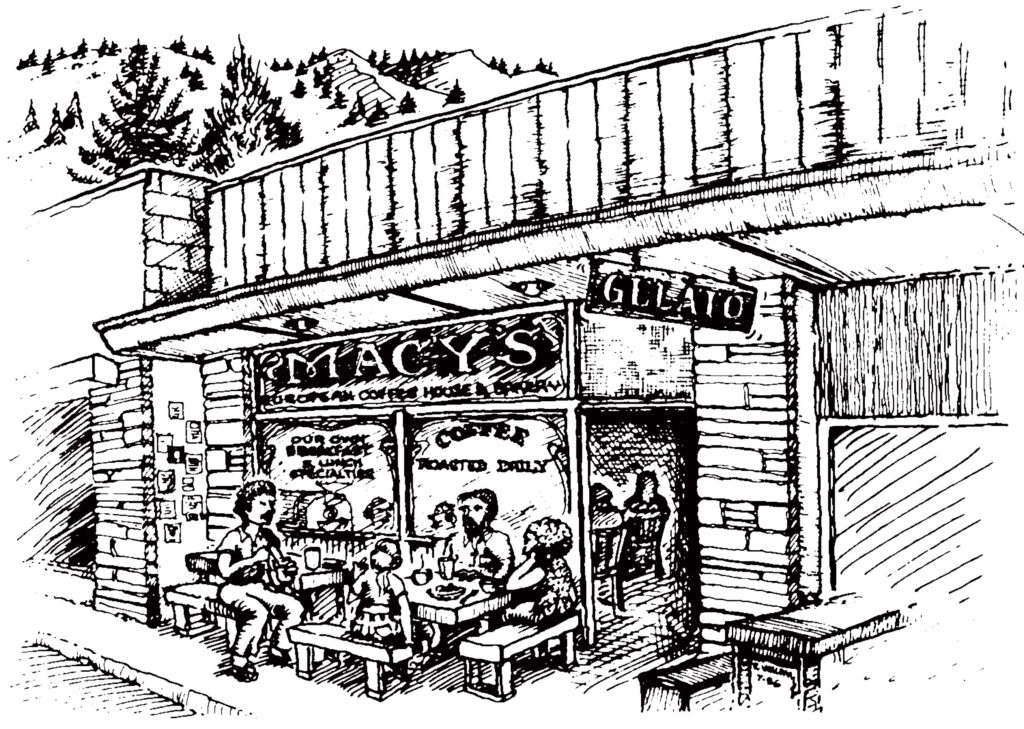

Waldmire, Bob to friends like Macy, led the push to preserve Route 66. He grew up along the iconic road, and later, as a gifted illustrator, captured college town landmarks and local businesses like Macy’s—snapshots in time. His first drawing of Macy’s in 1986 reflects the soul of its caretaker’s longstanding vision, and the anniversary shirts and mugs will bear said image. Waldmire also created the label for the bags of coffee beans Macy’s still sells in its storefront.

So, get your Macy’s gear and be a part of this landmark coffee shop’s storied history. A group photo of the Macy’s family—guests and employees—will be taken Saturday, Feb. 22, at 4:30 p.m. All are invited.

To learn more, visit www.macyscoffee.net